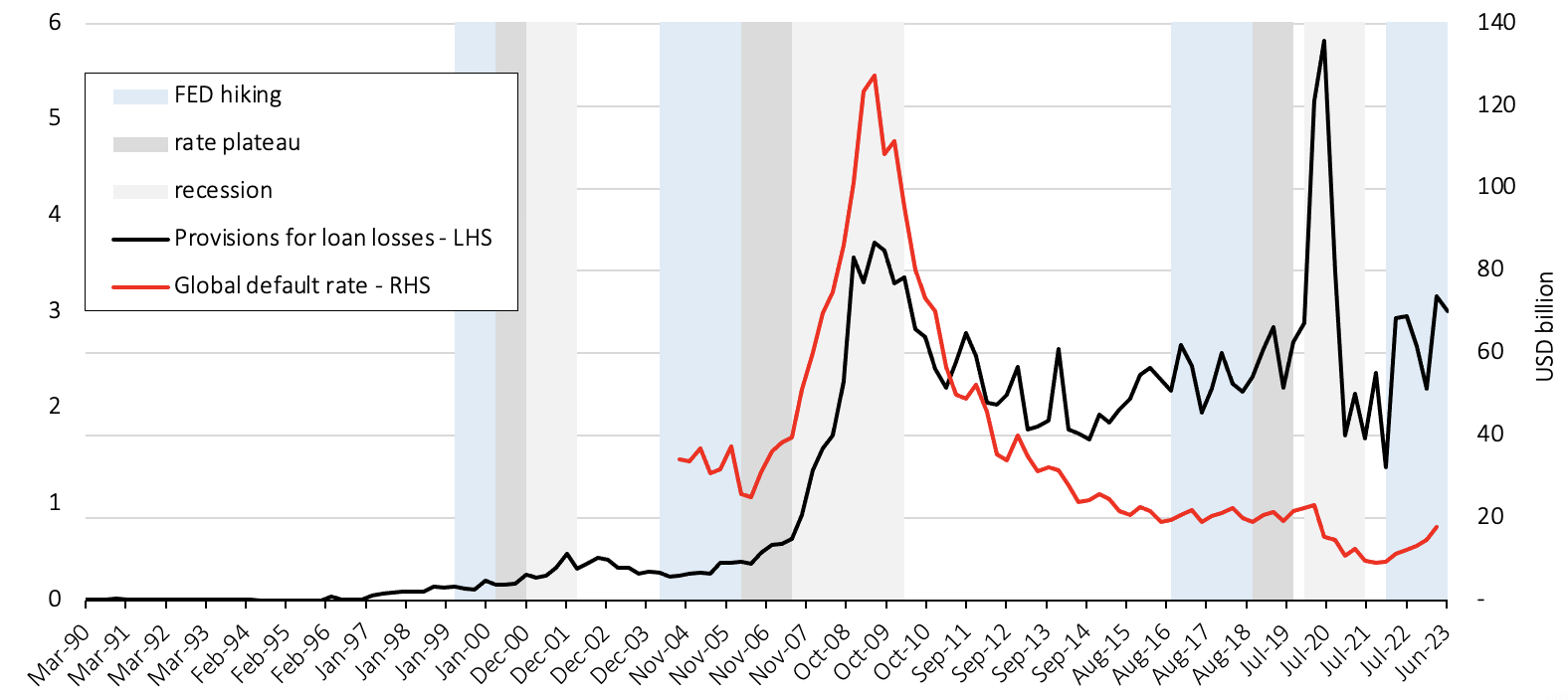

Takeaway: we look at the financial industry only to gauge its systemic stability, not as an investment target. The historical upside displayed by any of the players, even in a non-zero rates environment, has been consistently lower than the potential permanent loss of capital in case of default (see recent bank defaults in Switzerland and the US). Today, we think the global banking system is solid, with enough loan loss provisions stacked against very low global default rates, so far.

The recent default of Credit Suisse and a handful of US banks has sparked a debate that will probably never cease.

What we discuss here below is more philosophical in nature than financial, and the end of it is that there is no fix to the currently dysfunctional banking system of all modern economies. Because of that, we do not consider the financial industry as a potential investment target, but as an industry to watch for period disasters and their contagion effect on the wider global economy.

The crux of the matter is that at no point in time has any bank employee of any rank been charged criminally for any type of bank default. In a default shareholders lose their investment and customers lose their cash deposits, the textbook definition of a “permanent loss of capital”.

In his latest shareholder meeting Warren Buffett called for harsher punishment on those responsible for bank defaults. And he also said that nothing will ever change until such laws exist. In other words, all bank employees can gingerly continue operating with a short-term view of quarterly results and an aim to achieve their bonus targets, without any responsibility should these practices drive the value of the bank down. This is a modern-time oxymoron: why would governments consider banks “systemically relevant” if the people running them do not consider the social stability function these institutions perform? How can the bonus of the senior management be more important than the cash deposits of customers? Western governments have no answer to these questions.

The technical side of this pathetic state of things is that all Western banks found themselves in a tough spot when interest rates hiked fast in 2022. The root problem was the regulatory obligation to invest 100% of bank reserves in investment grade bonds or government treasury bills. These reserves are designed to cushion the gradual calls of deposits by customers – no bank has all its deposits in cash, ready for withdrawal, at any moment in its corporate life. Unfortunately, bond prices go down in a rate rising environment. So the value of bank reserves also when down fast in 2022. You only need one influential customer to challenge the solvency of a bank to produce a general crash in market confidence in that bank. This situation can turn quickly lethal for some banks, as Silicon Valley Bank learnt. The point to keep in mind is that all banks are in such situation, so the choice between default and business as usual rests uniquely on reputation.

These troubles are intrinsic to the banking business. The laws around it in the US and Europe are also way too easy to impose more conservative managerial styles, nor is the political environment conducive to adopt punishments for delinquent mismanagement. Such political support would need to challenge too many entrenched traditions, relations, interpretations. It may sound pessimistic, but the banking system will continue being the Achilles heel of Western economies, and there is nothing anybody can do to fix it during our lifetime.

In our investment view, the current way the financial sector is designed represents more a liability than an asset. At Index & Cie we do not touch legacy financials of any kind, including insurance. However, this exclusion provides no protection when the periodic banking catastrophe hits, as contagion usually spreads to every other industry.

Despite the current design, recent events do not make us fear a banking crisis is afoot. In fact, higher rates give a long-awaited breath of fresh air to banks, once the transition to a world of higher rates is completed. Concurrently, banks seem to be well defended against a possible rise in defaults due to higher rates – see graph below.

Provisions for loan losses – top 100 banks by market cap, all higher than USD 20bn (in their respective listing currency)